I think we need to say it upfront that all data is *much* greater than what people call big data. As someone who works with data in development space, I believe in the use of all data.

That’s why its imperative to understand “

Increasingly conversations about possibility of big data playing an emerging role in solving development challenges has me, like few others, unsettled. Just because it has the term “big” in front of data does not mean its “all” data. There are many definitions that exist of big data. See here 40 such definitions. The common theme between them, for me, is that this data is ‘analyzable’ by machines to derive meaning from it.

This is problematic, for a few reasons:

1. Firstly, there is still significant amounts of data that are not digital. Sure, we are seeing digitization of data increasingly but that does not mean all data is digitized or in an analyzable format today. Therefore, whatever constitutes the universe of ‘big data’ is a subset of ‘all data’.

2. Secondly, digital data that is being created every second does not represent “all” and definitely not “us”. So any analysis that results to public policy application will definitely not be reflective of the “us”. This is captured well by Nick Couldry in A necessary disenchantment: myth, agency and injustice in a digital world

A new myth about the collectivities we form when we use platforms such as Facebook. An emerging myth of natural collectivity that is particularly seductive, because here traditional media institutions seem to drop out altogether from the picture: the story is focused entirely on what ‘we’ do naturally, when we have the chance to keep in touch with each other, as of course we want to do.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

com/doi/10.1111/1467-954X. 12158/abstract

3. Thirdly, its a myth that big data is generating entirely new and better forms of knowledge which will help solve development issues. This is the most problematic in the field of public policy. As Nick Couldry puts it:

” analysts are giving up on specific hypotheses and instead

focussing on generating, through countless parallel calculations, ‘a really good proxy’ for whatever is associated with a phenomenon, and then relying on that as the predictor. ”

The implication of development policy-making based on ‘real good proxy’ sends nervous shivers down my spine.

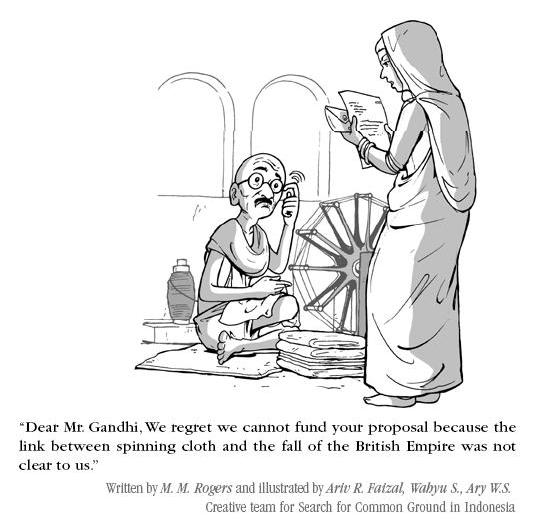

4. Lastly, to me, there is a power differential that is at play in what the ‘data’ in the big data represents. Whose data (digital haves vs digital have-nots), who analyzes (digitalsavvy-haves vs. digitialsavvy have-nots) and how its analyzed are all subject to the biases and power relations that exist in the real world ‘we’ inhabit.

These reasons are important to remember as we invest time, energy and money in making arguments about ‘big data’ in development discourse. There are challenges that with timely, relevant data analysis may be met but development challenges are not always wanting of faster analysis but are results of long standing socio-economic-political power struggles which no matter how fast and timely analysis you produce will not be solved because of that analysis.